By JOHN LOH and WONG WEI-SHEN starbiz@thestar.com.my

Although still at an early stage, they can make a difference in addressing social issuesPROFIT with a conscience - that could well be the mantra for a new kind of business taking root here called the social enterprise.

Although there is no one definition, social enterprises are generally understood to be businesses that exist primarily to fulfil social goals, which could be anything from reducing poverty, creating jobs for the disadvantaged, to educating children in rural areas.

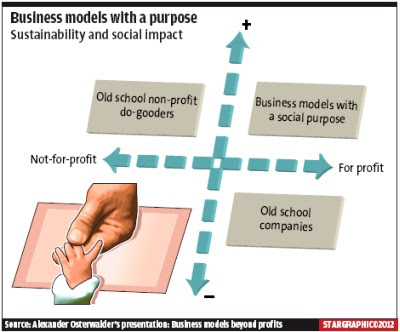

According to Leaderonomics

chief executive officer Roshan Thiran, a social enterprise bridges the gap between a traditional

non-profit organisation and for-profit corporation (

see chart).

In fact, he points out, all businesses start out with some kind of social mission in mind, like how

Google was premised on organising information on the Internet, and Ford on making cars that were affordable to the masses.

To accomplish its social objectives, a social enterprise has to find ways to generate income by providing a product or service, and the resulting profits are funnelled back into a specific cause.

Unlike a non-governmental organisation or charity, social enterprises do not rely on donations, but they may seek grants, equity, or loans to support their capital needs.

Kal Joffres, chief operating officer of the Tandem Fund, says that in any case, “there isn't enough free or donor money to go around to fix the problems we have today”. Tandem Fund is a not-for-profit venture fund that invests in social enterprises in Malaysia.

It can be hard to change the mindset of existing leaders, but what we can do is create leaders from the youth. - ROSHAN THIRAN

It can be hard to change the mindset of existing leaders, but what we can do is create leaders from the youth. - ROSHAN THIRAN

“

Social enterprises are still at a very early stage, but they could be very transformative for a lot of the problems we face,” he contends.

Due to their non-traditional structure, social enterprises tend to take innovative approaches around their business model.

In the case of Leaderonomics, which got its seed funding from

Star Publications (M) Bhd,

The Star's parent shareholder, a part of the proceeds from its training and human resources consultancy work done for corporates is reinvested into its youth leadership-building activities.

For example, the company organises regular leadership camps for young people where half of the spots are reserved for orphans and

underprivileged children.

In addition, it opened a youth community centre for “kids-at-risk” called DropZone in

Petaling Jaya and is piloting a leadership club for secondary schools.

Leaderonomics' main aim, Roshan says, is to build leaders from the grassroots. “It can be hard to change the mindset of existing leaders, but what we can do is create leaders from the youth. If we are successful in changing their value system into one that is authentic and based on integrity, we have a shot in 20 years to see many leaders in the country emerge from this group,” he says.

To supplement its core mission, it offers a range of consultancy services, such as its talent accelerator programme for those identified as an organisation's “top talent”, and it counts companies like Malakoff,

RHB Bank, and

Sime Darby among its blue-chip clients.

“Social” returnsIn the 1980s, General Electric boss and maverick management guru

Jack Welch introduced the idea of “shareholder value” which dictated that a company is duty-bound, above all else, to maximise returns on investment (

ROI) for its shareholders, increase its share price, grow its market capitalisation and so on.

Turning this concept on its head, social enterprises measure themselves against a different set of criteria, using terms like social ROI, and the triple bottomline, referring to people, planet, profit.

I think paying taxes makes us more powerful. We are on the same footing as any other business. - DR REZA AZMI

I think paying taxes makes us more powerful. We are on the same footing as any other business. - DR REZA AZMI “Things like marketing and branding, they are not real. But if you can create lasting social value, I think the community will (continue to) give back,” Roshan quips.

Most social enterprises, it would seem, have one thing in common: they were motivated by a problem.

Online crafts retailer Elevyn - whose name was derived from the phrase “the eleventh hour” - started out this way.

One of its founders, Puah Sze Ning, was volunteering with the orang asal in

Sabah as part of efforts to document land rights issues and the displacement of local communities when she was asked by one of the women if she could help them sell their handmade crafts in

Kuala Lumpur.

“They were really poor - some are single mothers, some are elderly. And they have no other source of income,” explains

Mike Tee, co-founder of Elevyn with Devan Singaram.

“Even when they make it, they can't really sell it as Sabah has a very limited market. Sze Ning was quite stumped, she had just finished university at the time. So she came back and felt really helpless.

“During one of our meet-ups, she told us this story. Since we're (Tee and Devan) both software developers, we thought about setting up a website that would connect producers to customers.”

The term “orang asal” refers to all indigenous people throughout Malaysia, while “orang asli” refers to those in the peninsula, Tee says. The website,

elevyn.com, sells a variety of fair trade items, and it is worth noting that beside each product display is a box that shows exactly what percentage of its sales price goes to the maker, designer, reseller and for materials.

They were really poor - some are single mothers, some are elderly. And they have no other source of income. - MIKE TEE

They were really poor - some are single mothers, some are elderly. And they have no other source of income. - MIKE TEE

“We started with a group in Kudat, Sabah, then expanded to the peninsula with a couple of orang asli groups. Recently, we started working with Burmese refugees based in Kuala Lumpur. People have described us an ebay for the poor,” Tee chuckles.

To get on their feet, the team applied for and won a RM150,000 grant from the

Multimedia Development Corp (MDEC) in 2008. At the time, MDEC gave out pre-seed funding to start-ups with technology businesses.

On Elevyn's business model, Tee points out that some 70% to 80% of the sales price goes back to the producers of the goods, and the team receives a 5% cut after deducting PayPal transactions.

“We make very little money from this. That's why for this model to work, we need scale,” he says. A percentage of the profit is also apportioned for a particular cause like school books, for instance.

Currently, Elevyn either sells individual products to visitors at its website or bulk orders directly to corporate clients. They have yet to sell to gift retailers, but Tee says this might be a possibility in the future.

However, several operational hurdles stand in its way. First, the products must address market needs. “Sometimes we tell our producers to make a product this way or that to suit the market, but what they are making could have been passed down from their ancestors, and we certainly don't want to disrupt that,” Tee explains.

Second, constant supply is difficult to ensure, since most of the orang asal depend on the rattan and other raw materials that grow near their homes, which, in turn, may be determined by the seasons.

Profitable venture?A rented home in Sri Hartamas serves as an office for Wild Asia, a social enterprise that advises clients on environmental and social policies and practices.

“We have been profitable since we started,” exclaims

Dr Reza Azmi, Wild Asia founder and director.

“We are service-based, and so did not require a lot of capital,” he says of the enterprise that started out as an online platform for information exchange on nature-related issues.

Some of Wild Asia's services include sustainability assessments to help plantation companies comply with standards set by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, as well as developing their environmental and social management systems.

Social enterprises are still at a very early stage, but they could be very transformative for a lot of the problems we face. - KAL JOFFRES

Social enterprises are still at a very early stage, but they could be very transformative for a lot of the problems we face. - KAL JOFFRES This social enterprise got off the ground some 10 years ago with RM10,000 in seed capital from a few individuals, including Reza. Wild Asia, which he says has close to RM1mil in paid-up capital now, is based on a model whereby 65% of its profit goes to its cash reserves as well as to invest in responsible tourism initiatives, such as the Okologie dive and study centre at the Batu-Batu Resort in Mersing, Johor.

A further 25% of its profit is shared among staff and associates as a bonus, while the balance 10% is split between Wild Asia's shareholders.

Reza, who studied biology in the United Kingdom, says he found his calling in conservation work during a gap year from university. “I wanted to be a professional beach bum,” he jokes.

Having done this for a number of years, he observes that there has been growing concern among businesses to preserve the natural world. “Banks and investment houses are starting to take notice. They might refrain, for example, from putting their money in or lending money to companies that deal with converted forests.

“We are one of the groups they hire to verify these things. But its the foreign banks that have specific policies on this,” Reza explains.

Even so, profitability remains a key concern for social enterprises. According to Tandem Fund's Joffres, start-ups break even in about three to five years, but social enterprises can take up to eight years.

“It takes them (social enterprises) longer to grow the market, and they often take smaller margins and do community-building activities at the same time,” he quips. Compounding this is the issue of funding, which can be hard to come by for social enterprises.

The tax questionAnother issue that could curtail the growth of social enterprises is the lack incentives and tax breaks. They can currently only register as private limited companies and are taxed as such, since they derive an income from business activities.

Tee says Elevyn is taxed on a percentage of its profits, though not if the company is loss-making. To make things easier for social enterprises, the Social Enterprise Alliance, where Joffres is a committee member, is pushing for more policy recognition for the sector.

For starters, it is hoping to make amendments to the tax policies to make it legal for charitable trusts or foundations to give money to social enterprises.

Foundations cannot provide monetary support to social enterprises under the present tax regime as it would be viewed as an investment by the Inland Revenue Board (IRB), Joffres stresses.

Deloitte Malaysia country tax leader Yee Wing Peng tells

StarBizWeek via email that while the Government does provide for tax exemptions on income received under the Income Tax Act 1967, this is for approved charitable organisations.

“A limited liability company or Sdn Bhd is not included because it is formed with a profit-seeking motive and the profits generated can be returned to shareholders in the form of dividends. There is no restriction to prevent the company from distributing profits to the shareholders instead of using the profits solely for charitable purposes.

“I advise the social enterprises to use a legal form that is acceptable to the IRB as this would encourage more donors to contribute due to the availability of tax deduction and with the income exempt from tax, more funds can be channelled for charitable causes.

“If the initiator has to use a Sdn Bhd set-up due to compelling business needs, attempts may be made to the higher authority i.e. the Finance Minister to consider exemptions. Putting in place covenants to ensure that the profits made by the Sdn Bhd can only be used for the intended charitable purposes may help,” Yee explains.

Nonetheless, Wild Asia's Reza argues that social enterprises “don't need handouts to survive”. “I think paying taxes makes us more powerful. We are on the same footing as any other business. You are a business entity just like any other,” he says.

More than moneyA key question moving forward for social enterprises will be how sustainable they can be, and what kind of impact they can deliver. That will depend on, among others, how quickly they can adjust their business models to respond to market forces.

Asked about Wild Asia's impact, Reza says it has been the cultural shift within organisations in their treatment of the environment. He cites the example of a major government-linked corporation they had consulted that now has its own 20-man team to do the job internally.

He also notes that Wild Asia is beginning to attract interest from disillusioned corporate dropouts wanting to join his team and do something with a purpose other than financial gain.

According to Tee of Elevyn, the impact of a social enterprise need not be purely financial either. “You can't fix a problem just by putting money into it,” he says.

“There was recently an order that came in from Japan and Spain. We told them (the producers) to ship it to these addresses and the women were very surprised, because to them these countries are a world apart, and yet they had an interest in their products.

“The impact is not just in terms of money, but also the pride that what they're making has value.”

Related Stories:Creating an impactInvesting in the right causesSEA says some local enterprises are ready for investors Related post: